Policy paper

A new day for community energy in Europe

This post is based on an article written for and published by Energy Transition.

The three EU institutions have finally agreed on a new Renewable Energy Directive, which will determine how renewables in Europe are rolled out through 2030. With it comes new opportunities for Europe’s growing community energy movement. National governments must now support it.

There is a distinct lack of political leadership on renewables in Europe at the moment. The latest debate on what Europe’s ambition for renewables should be up to 2030 has just been agreed, but it is far from where it should be. Despite so many figures that demonstrate costs are coming down, most EU Member States have been stubbornly focused on maintaining a European target that is even below business as usual at this point.

The German government, the Originator of the Energiewende, now looks more like a boat drifting aimlessly at sea, failing to deal with its own internal energy issues, and creating problems on the European scene. It is still trying to undermine the agreement – targeting collective self-consumption in particular – that was reached between the European Parliament and the Council in the early hours of 14 June because it does not like the deal that was made.

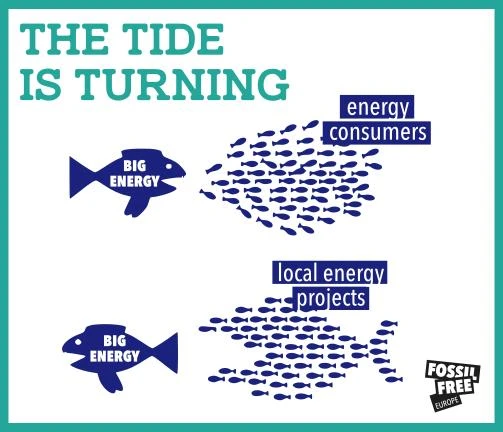

This current dynamic overlooks a small but key player in this whole story: the European citizen. Before Germany thought up its Energiewende and Denmark outlawed nuclear in its constitution, it was the citizens that built the first wind turbines to produce renewable electricity. They did this by creating cooperatives, or ‘renewable energy communities’ as they are now called with the likely conclusion of the new Renewable Energy Directive.

Where we have come from

At the end of November 2016, the European Commission made an unprecedented move by proposing to acknowledge citizens (as ‘active customers’) and energy communities in EU legislation as legitimate market actors in the energy transition. And it could not have come at a better time.

Without any formal recognition at European level, and with limited or no recognition at national level, community energy has been ever-growing since the 1970s. Moreover, a European movement has really begun to expand in the last decade. Community initiatives have fought against opposition from national governments, regulators, system operators, and utilities, many failing but many also succeeding. As of the end of the 1990s, in Denmark energy communities owned 70-80% of the installed wind capacity, while in Germany at the end of 2017, around 42% of installed renewables capacity was owned by citizens in one form or another.

Yet, this movement has been under stress. After 2000, communities in Denmark have been mostly pushed out of the market. This led to national legislation in 2008, which attempted to give citizens a stake in local renewable projects, but this has not solved all problems. The development of renewable energy cooperatives has also slowed due to the development of more market-based mechanisms for renewables, such as auctions and tenders. The market for renewables in Europe has developed without acknowledgment of energy communities, and if it continues the energy transition could face major growing pains moving forward.

Therefore, 14th June 2018 may come to mark an important milestone in the energy transition. Before this date, citizens and communities have been unsung heroes - even pioneers - of the energy transition. This is the date when the Council and the European Parliament finally agreed to give energy communities and citizens not just acknowledgment, but a concrete set of rights and an enabling framework so they can develop at national level.

What do communities now have to work with

Much of what was agreed needs to be further analysed. Nevertheless, some very important elements can already be identified:

Acknowledgment

In order to provide energy communities with support through an enabling framework, governments must first understand what an energy community ‘is’. Therefore, it was always going to be necessary to get the definition right. The main challenge was to make the definition flexible enough to allow for different configurations consistent with the different company laws across the EU, while also ensuring the definition was not so broad that it could be abused by larger energy companies looking to rebrand themselves or gain a competitive disadvantage.

To a large extent, this balance has been achieved. The definition of a renewable energy community ensures that communities are legal entities that are autonomous – both from an internal perspective to ensure democratic governance, and externally to ensure the community does not become beholden to outside finance or business interests. The definition also ensures local control, that they are open for any local citizen to participate, and that they are primarily aimed at providing community or local benefits rather than financial profits.

Lastly, renewable energy communities are open to membership or control by natural persons or local authorities, opening up new opportunities for collaboration between local governments and citizen initiatives.

New rights and enabling frameworks

The new Directive will now also include a number of rights and provisions that will support the development of enabling national legal and regulatory frameworks for renewable energy communities.

First, every final consumer will have a right to participate in a renewable energy community without having to worry whether they will keep their traditional consumer rights.

Member States will also be required to assess both the potential and the existing barriers to the development of energy communities. From this assessment, they will need to develop a framework that allows renewable energy communities to access all markets without discrimination and on a level playing field, including through proportionate and transparent procedures and charges.

Beyond these broad provisions, renewable energy communities will have a right to set up energy sharing arrangements. Member States will also need to ensure citizens that are vulnerable or energy poor benefit from participating in a renewable energy community, and that public authorities get regulatory and capacity building support to participate. Lastly, Member States must put in place tools to facilitate access to finance and information – two key impediments for new renewable energy communities. Going forward, citizens and communities should be confident that they can get information on their rights.

Access to renewables support schemes

Perhaps the biggest threat for renewable energy communities at the moment is the development of auctions and tenders for new renewables installations. There is a lot of evidence that such methods of determining eligibility for support is not appropriate for smaller market actors, and renewable energy communities in particular.

The Renewable Energy Directive will not solve this problem. However, it will require Member States to take the specificities of renewable energy communities into account when designing their support schemes. Therefore, there is an opportunity at national level for renewable energy communities to advocate to their governments for support schemes that allow them to access support on a level playing field with traditional energy companies.

The big fight here will come with the revision of the European Commission’s Guidelines on State aid for environmental protection and energy. DG Competition is currently taking steps to update the guidelines beyond 2020, and gaining further recognition for energy communities under the new guidelines will be essential in ensuring energy communities can have equitable access to available renewable support schemes in the next decade.

The big fight over self-consumption

Providing strong rights for renewables self-consumption proved the most contentious issue around citizen energy in the trilogue negotiations. Nevertheless, citizens have come away with strong rights to consume, store and sell their self-produced renewable energy. They have a right to access the market, they can be confident that they will not face discriminatory procedures and charges, and they will now enjoy a right to engage in peer-to-peer energy sharing.

For self-generated renewables that are consumed onsite without entering into the grid, self-consumers also have a right not to be charged any tax or levy. Only under certain circumstances may Member States impose charges. Unfortunately, tenants in multi-apartment buildings will not be able to enjoy this right rights as other citizens. This will likely limit potential, and will create fairness issues. Nevertheless, Member States must reduce barriers for tenants, as well as vulnerable and low-income households, so that they can become self-consumers.

Where do we go from here?

Now, the important task is to communicate these new opportunities to citizens across Europe, and to ensure they can now understand and actively use the new rights they have been granted.

The new Renewable Energy Directive does not solve all problems for renewable energy communities, and indeed there are a lot of unanswered, and indeed new, questions to unpack. However, it is undeniable that we have come a long way since this process started. Virtually overnight, energy communities have gone from having no explicit status to obtaining an important basis for taking on a very active role in Europe’s energy transition.

The debate around climate and energy leadership will not wane at the European level. If and where national governments fail to lead, citizens are ready to take the reigns. For the first time, they are now backed by European law. However, now they need the support of their national governments. Continued support from some of the first movers in citizen energy, especially Germany, wouldn’t hurt either.