Policy paper

Europe’s new energy market design: What does the final piece of the Clean Energy Package puzzle mean for energy democracy?

*This post is based on an article written for and published by Energy Transition.

At the end of 2018, EU legislators finally hammered out a political agreement on a new energy market design. As the dust settles, it’s time for a preliminary assessment to determine whether, at least on paper, all European citizens and communities now have the tools to take ownership in the energy transition.

Europe’s new energy market design: finding a new approach

Europe’s energy policy has been outdated for a while now. Regulation still supports a centralised energy system dominated by large energy companies that produce power from dirty fossil fuels and inflexible and expensive (both to consumers and planet) nuclear energy.

If we want to avert the more severe impacts of climate change, we need to rapidly decarbonise our energy system. The good news: the momentum is there. Renewables are becoming more cost-competitive and flexible, the energy system is becoming more decentralised, and technology now allows citizens to get actively involved – both individually and collectively through community energy initiatives.

This trend will only continue. According to a CE Delft study, almost half of EU households could produce renewable energy by 2050, about 37% of which could come through involvement in a renewable energy cooperative (REScoop). Moreover, if demand response, energy storage and energy efficiency are factored in, 83% of Europe’s citizens could be active in the energy sector by 2050.

In order for Europe to realise this potential, regulation and policy needs to catch up with reality. The market is currently incapable of valuing benefits that renewables self-consumption, flexibility, and storage can provide. Individuals and communities that participate in the energy market have been treated, at best, as an afterthought and, at worst, a threat to be quashed. At the same time, governments are further distorting the market by introducing new ‘capacity mechanisms’ that remunerate dirty power plants to sit unused, at consumers’ expense.

Energy democracy – not just the market – as an essential ingredient for a successful transition

Renewable energy cooperatives have waited with cautious optimism for the conclusion to Europe’s most consequential energy legislation overhaul yet: The Clean Energy for All Europeans Package.

Much anticipation has built up around what is arguably the most transformative concept in the entire package: the acknowledgment and support of active energy citizens and communities as stakeholders in Europe’s energy market.

The final political agreement between the EU legislators is far from perfect. Nevertheless, together with the recast Renewable Energy Directive, which we summarised not too long ago, the new market design offers opportunities for citizens and their communities to participate across the energy sector.

Why is this so groundbreaking? Just for some perspective, consider this: in the EU’s Third Energy Package (concluded in 2009), active energy citizens were not mentioned even once. Now, citizen participation is one of the governing principles upon which the EU’s energy market will operate. This means citizens and communities should have an equal and fair opportunity to take advantage of many other progressive elements in the market design such as dynamic energy contracts, participation in demand response, and access to independent aggregators (that is, a third party that packages together small amounts flexibility or production so they can participate in larger markets).

So what is in the new market design for communities? Below are just some of the more interesting details.

The Good

Acknowledgment

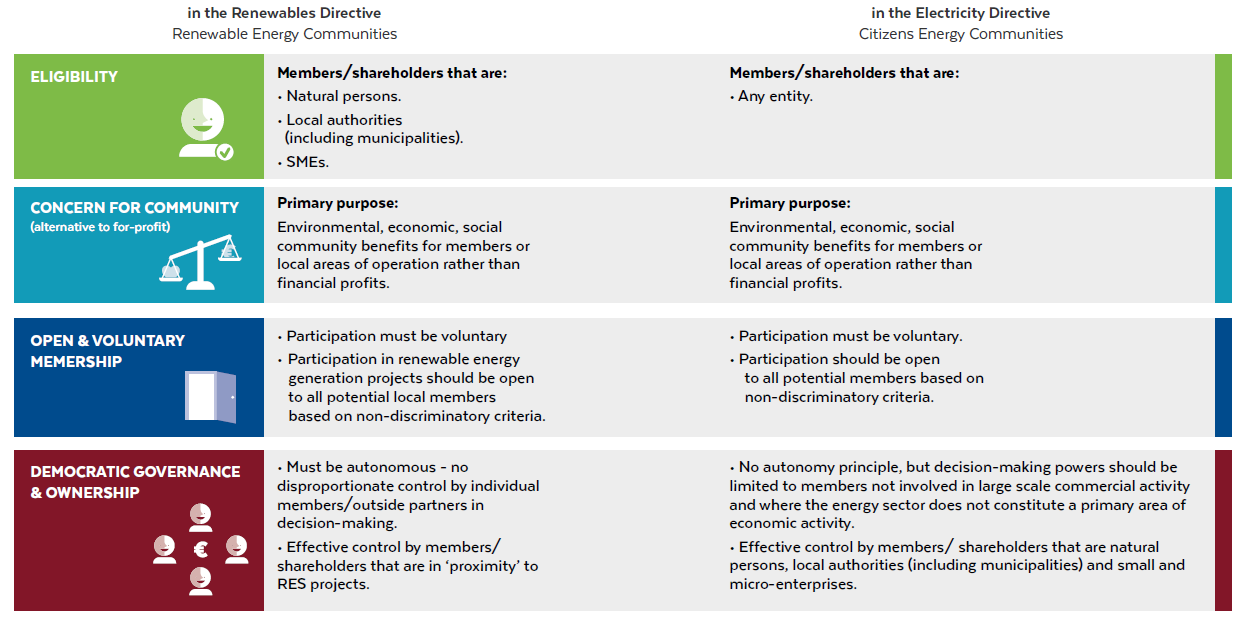

Similar to the Renewable Energy Directive, which defines ‘renewable energy communities’ (RECs), the recast Electricity Directive now contains a definition of ‘citizens energy communities’ (CECs).

Significantly, CECs are defined as a type of market actor based on a particular type membership, governance and purpose, which are different from traditional profit-oriented energy companies. Based on these characteristics, the definition establishes criteria for different legal entities to meet in order to be eligible for the status of CEC. The definition makes clear that CECs can focus on pretty much any activity throughout the power sector.

Definition of Citizens energy community under the provisionally agreed Electricity Directive:

"citizens energy community' means: a legal entity which is based on voluntary and open participation, effectively controlled by shareholders or members who are natural persons, local authorities, including municipalities, or small enterprises and microenterprises. The primary purpose of a citizens energy community is to provide environmental, economic or social community benefits for its members or the local areas where it operates rather than financial profits. A citizens energy community can be engaged in electricity generation, distribution and supply, consumption, aggregation, storage or energy efficiency services, generation of renewable electricity, charging services for electric vehicles or provide other energy services to its shareholders or members"

Originally, the Commission proposed ‘local’ energy communities. The change to ‘citizens’ is a significant win as it sends a political signal that this initiative aims to support business models based around entities whose purpose is to provide services to members or other community benefits, where the ownership and control is with citizens, small businesses and local authorities.

The originally proposed definition, while still focusing on citizen ownership, gave a more techno-centric connotation. It could have simply been used by large industrial players to lobby for special privileges to set up micro-grids and avoid paying grid fees, or help energy companies create and control local energy management systems in order to sell new services. At the very least, the name gave the impression that energy communities are activities-based (for instance around micro-grids or collective self-consumption), rather than a way to self-organise citizen ownership and control – a misperception that remains to this day.

In reality, EU law already supports the establishment of local energy systems (also called closed distribution systems) by larger businesses. Furthermore, other provisions from the Clean Energy Package, for instance provisions on active customers and renewables self-consumers, provide more than ample opportunity to energy companies that want to offer innovative services to consumers. For the purpose of the Directive, the CEC definition ensures that certain types of citizen-owned initiatives, along with their added value and challenges, have special acknowledgment so they can participate across the market on a level playing field with other market actors.

The one significant shortcoming with the CEC definition was the failure to ensure that they are autonomous in their decision making from individual members. In the Renewable Energy Directive ,this safeguard – which is contained in the definition of RECs – ensures democratic governance, preventing members that have more resources to invest, such as larger companies, from exercising disproportionate influence within the community.

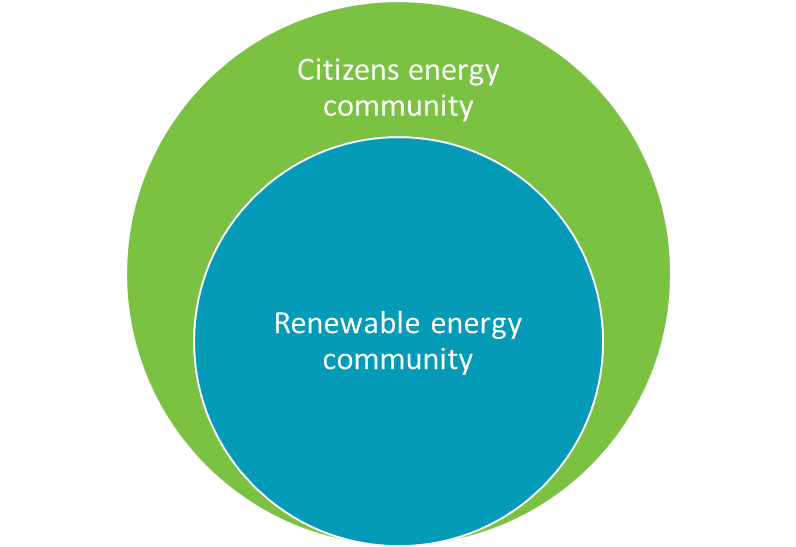

Now, a significant question that often arises for many is: what exactly is the relationship between the REC and CEC definitions?

For the most part, the two definitions express one coherent concept: a way to organise community ownership of energy to meet environmental and socio-economic needs. Activities aside, at their core CECs and RECs represent a different type of market actor. In contrast to traditional profit-oriented energy companies, CECs and RECs are based on a set of operating principles that emphasise open, democratic participation. Furthermore, instead of aiming to make profits, they deliver services or socio-economic and environmental benefits to their members or the local community. Not surprisingly, many of these principles are based on the seven international cooperative alliance principles.

Together, the two definitions represent a holistic recognition and support for this type of ownership not just in renewables, but across the market including energy efficiency, distribution grid operation, electro-mobility, supply, aggregation and other energy-related services and activities.

In conclusion, we can say that the relationship between the two definitions is quite clear: RECs represent a subset of CECs. Whereas CECs are intended to be able to participate in activities across the power sector, RECs are primarily focused on activities relating to renewables at the local level. The eligibility criteria for being recognised as an REC are also stricter than for a CEC, particularly with regard to democratic decision making (i.e. autonomy). In this sense, RECs can be seen as the gold standard for a CEC.

Supporting citizens energy communities to participate in the energy transition

Like the Renewables Directive, the market design includes supportive elements to ensure that, as a different type of market actor which experiences distinct challenges, CECs can participate across the market on a level playing field.

Most importantly, CECs will have a right to ‘equal’ and ‘proportionate’ regulatory treatment. This is important because the EU legal principle of equality requires similar market actors to be treated similarly, while different market actors need different treatment.

During the negotiations, incumbents argued strongly that CECs should abide by the same ‘free market’ rules as larger energy companies. As a different type of market actor, subjecting CECs to the same rights and responsibilities as larger profit-oriented energy companies would be overburdensome and discriminatory. Ensuring proportionate treatment for CECs will help allow them to operate on a level playing field in the market with other bigger market actors.

In line with the above, Member States are required to maintain priority dispatch for smaller renewable generation projects up to 400 kW at least until 2026. This will ensure that smaller CEC and REC projects can feed generated electricity from renewable energy sources into the grid. These same thresholds will apply to exemptions from balancing responsibility. CECs with generation above these thresholds will be able to choose whether to take on this responsible directly – or whether to delegate it to a third party.

Member States must also set up enabling national frameworks and guarantee a set of rights for CECs and the individuals that participate in them. This will shield CECs from discriminatory or overly-burdensome hurdles, while also ensuring individual citizens don’t lose their consumer rights by participating.

Moreover, CECs will have a right to share energy, while network operators will be required to help facilitate this activity. While many technical and practical details will need to be worked out at the national level, energy sharing provides numerous opportunities for citizens living in the same areas (e.g. apartment or shared buildings, neighborhoods) to innovate with renewables and other flexible clean energy technologies like storage. In particular, energy sharing could allow CECs to innovate in the creation of solidarity mechanisms for benefit sharing to make it easier for vulnerable and low-income households, and those living in social housing, to participate.

Finally, national energy regulators will have a duty to monitor the removal of unjustified regulatory and market barriers for energy communities at the national level. This will allow decision makers to gain a better understanding of the added value of CECs and the challenges they face.

The Bad

Community networks

One of the big opportunities for citizens coming out of the Commission’s original legislative proposals was the possibility for CECs to have a right to set up, own and operate local power networks, or ‘community networks’. However, this was heavily fought against by incumbent distribution system operators (DSOs) and Member States. Unfortunately, according to the final agreement, it will be optional for Member States whether to grant CECs with this right. Many Member States are likely to ignore this opportunity.

Transparency and accountability?

Furthermore, there is the issue of transparency. In the Renewables Directive, Member States have to report on the measures they put in place to ensure RECs have a supportive enabling framework. There are no such provisions in the market design, and there are only vague planning and reporting provisions relating to consumer participation in the new Energy Union Governance Regulation. This raises the question of how citizens will be able to hold their governments to account on one hand, and how the EU Commission will oversee and enforce provisions on CECs on the other.

Subsidies for dirty fossil fuels

The biggest fight in the negotiations was over the role that fossil fuels should play in ensuring enough electricity is supplied to meet demand as more renewables come onto the system, namely through ‘capacity mechanisms’.

Importantly, Member States will be required to critically assess whether such mechanisms are needed, and to exhaust other options before a capacity mechanism is adopted. Furthermore, capacity mechanisms must meet certain CO2 limits and be open to competition from other technologies.

While this will be overseen by the EU, there is little the Commission can do if a Member State implements a capacity mechanism that is not warranted. Furthermore, loopholes such as exemptions for installations finished before 2020 and CO2 limits that only apply to existing installations after 2025, allow new coal power plants to benefit from these mechanisms at least until 2035. Capacity mechanisms will impose a huge cost to consumers, and will slow the pace of coal phaseouts that are crucial for fighting climate change. There is also a risk that these market distorting mechanisms will limit the effectiveness of new rules to encourage and incentivise energy efficiency and flexibility by individual citizens and CECs.

The messy

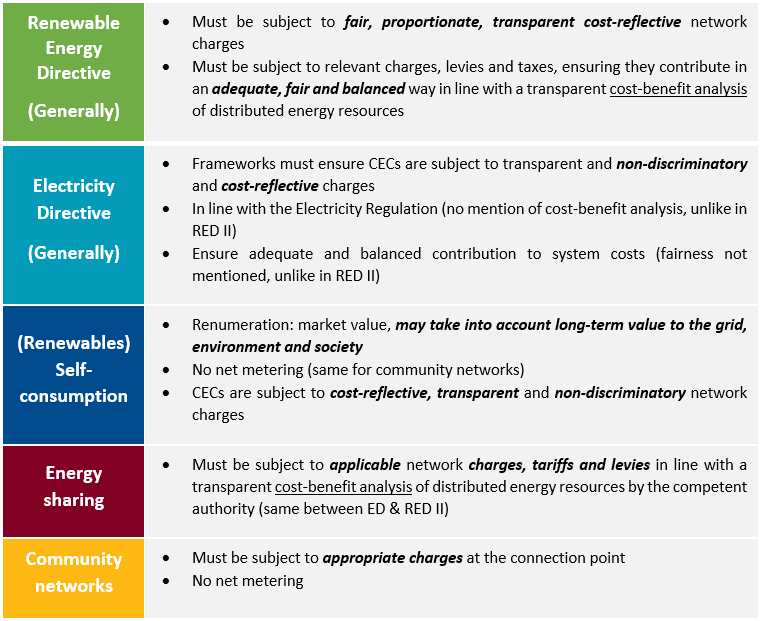

One issue that will be critical in determining whether CECs can meaningfully invest and take ownership in the energy transition is network charges. Simply put, this is what network operators charge to connect and use the grid. Along with taxes and levies charged by governments, network charges will make or break an economic business case for citizens to set up a CEC.

When it comes to determining network charges, the market design is very self-contradicting. Some provisions promote efficient and flexible use of networks, while others promote practices that would lead to inefficient use of the network. Therefore, the market design says everything and nothing, leaving the decisions to be made at national level.

When it comes to the calculation of network charges for CECs, there are different standards depending on the activity. It is fairly clear that RECs will have favourable conditions compared to CECs for how the charges they need to pay are calculated.

Notably, there is a requirement to determine grid fees for CECs that engage in energy sharing based on an assessment of their ‘costs’ and their ‘benefits’ to the system (i.e. cost benefit analysis). Ideally, if through their activities the CEC can save the DSO money this value should be reflected in the charges they pay to use the network. CECs can benefit the work of DSOs through efficient use that is optimal for operation of the grid, or by providing specific flexibility or other services to the DSO (for instance through new flexibility markets).

This concept, sometimes referred to as the “value of solar approach”, or “value of distributed energy resources approach,” is being developed in a growing number of states in the USA. Recently, Greenpeace EU tested the value of solar methodology in two regions of Spain. The concept clearly has potential value for utilisation in Europe.

Determining ‘who’ will pay for maintaining networks will be a monumental task – one which will play a significant role in determining how well DSOs (and also governments) get along with renewables self-consumers, CECs and other emerging market actors.

From paper to practice: now the real work begins

Overall, it was important to ensure that the market design legislation did not undermine the wins that were already made for self-consumers and RECs in the recast Renewable Energy Directive. If we take capacity mechanisms out of the picture, for the most part, this goal was achieved.

While imperfect, the new market design should be seen as a huge step change in EU energy policy. Never before was citizen or community ownership recognised in energy policy – yet as of today an entire framework has been created.

This new framework is also a key first step in challenging the existing orthodoxy that ‘the market’ should be the guiding hand of the energy transition. For the energy transition to be a success, all citizens and communities should have a fair chance to participate, even if it means creating a bike lane so that they can participate along with the bigger traditional market actors.

However, the real impact of the new market design will only be visible after Member States write the new EU rules into their national laws. Then we will have an idea of how transformative this new legal framework is likely to be. Success will be determined by the ability of citizens and communities to make their voices heard by their national governments, and for governments and regulators to take their commitments seriously, and prevent abuse.

A serious risk remains in the many Member States where citizens energy communities do not yet exist. In some cases national definitions and enabling frameworks will be created with little or no context. This could increase the potential for abuse of the citizen energy concept by other large market actors, or at the very least miss out on the social innovation potential. In other Member States, market incumbents could still try to impede the progress of CECs through tactical lobbying.

The transition to energy democracy will be long and hard. But the determination of citizens to help drive the energy transition is undeniable, particularly where they see a lack of action from their national institutions. As for its role, the EU has given citizens an early win.